Home | Research & Resources | Medicalisation of FGM/C

Key Findings

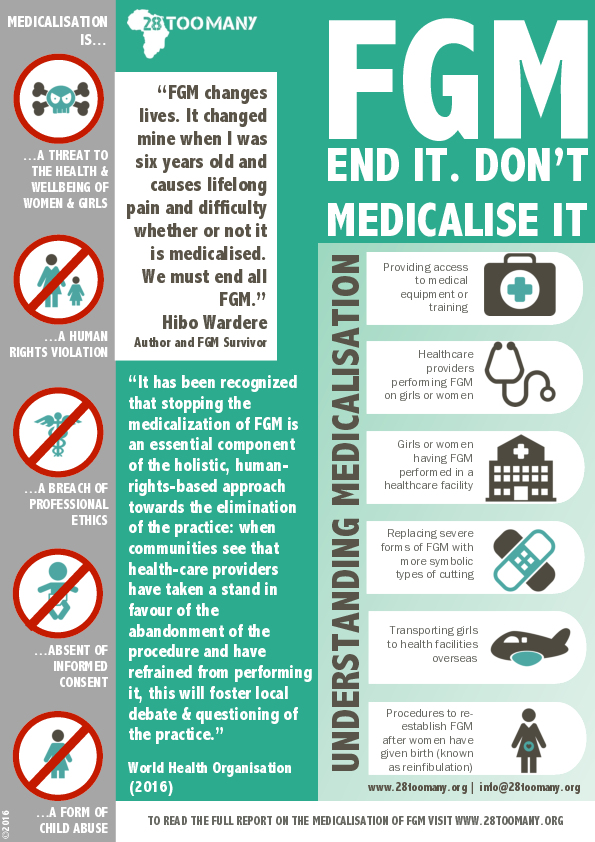

Medicalised FGM/C is an attempt to reduce the harmful consequences of the practice, but the effects of the practice remain despite it being performed in a medical setting and the gender inequalities that drive the practice remain in place through medicalisation.

Harm reduction

A growing number of families choose to have FGM/C conducted by a healthcare professional as a way of mitigating harm.

Use of language

Healthcare providers performing FGM/C on girls or women often utilise alternative language to avoid prosecution (i.e. genital modification).

Highest prevalence

Medicalised FGM/C is most common in Egypt, Indonesia, Kenya, Malaysia, Nigeria, Sudan and Yemen.

Symbolic cutting

Medicalised FGM/C is often connected with changes in type, replacing more severe types of cutting with symbolic cuts.

Medicalisation is not the answer

Medicalised FGM/C has increased in several countries, including Egypt, Indonesia, Kenya, Malaysia, Nigeria, Northern Sudan, and Yemen, with one-third or more of women in many of these nations having had their daughters cut by trained medical staff.

Medicalised FGM/C remains a very risky procedure and does nothing to mitigate the fact that this is a severe form of violence against girls and women, a violation of their human rights and has life-long physical, emotional and sexual implications for survivors.

The medicalisation of FGM/C is not an appropriate response to FGM/C. Not only does medicalised FGM/C still constitute a threat to the health and well-being of women and girls, but also it enables a practice that represents a deeply-rooted form of gender inequality.Furthermore, medicalisation hampers international efforts to eradicate FGM/C once and for all.

Medicalisation is driven by a desire for increased safety within the practice of FGM/C and can in some cases, be an unintended negative effect of FGM/C awareness raising that focuses on the harmful consequences of the practice for health.

.jpg)

_french.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

![Integrating the Prevention and the Management of the Health Complications [of FGM/C] into the curricula of nursing and midwifery Integrating the Prevention and the Management of the Health Complications [of FGM/C] into the curricula of nursing and midwifery](/media/uploads/Training Research and Resources/fgm_training_for_nurses_and_midwives_(who).jpg)